Just a quick break from doing research for my 21W.775 paper:

Joanna Macy is a buddhist with a serious interest in deep ecology and environmentalism. Her doctoral thesis involved a synthesis of general systems theory with Buddhist thinking. The publication Mutual Causality in Buddhism and General Systems Theory: The Dharma of Natural Systems looks like an interesting read.

Alright, back to work.

Saturday, October 27, 2007

Saturday, October 20, 2007

Deep Ecology

Hello and welcome again to Justin's endless effort to procrastinate less interesting work in favor of the quest for insight!

My 21W.775 - Writing about Nature and Environmental Issues, is the first humanities class I've taken at MIT that is NOT a philosophy class. Believe me ladies and gentlemen, that I would have never ventured outside the lofty domains of Course 24 - Philosophy and Linguistics, is it hadn't been for the wretched "HASS-D" requirement of MIT, that requires that I explore at least 3 flavors of the same ice cream: Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences.

What have I done to negotiate this forced exposure to other fields? Crafted the class into my own philosophy course of course! So far I've successfully been able to dictate my own philosophical-personal style of writing and have been received warmly. For an upcoming 10-12 page research paper, we've been asked to investigate some environmental issue of something relating to this area. My chosen topic is the Environmental Ethics of Zen Buddhism. Ha! Take that for forcing me to follow an assignment!

In my search for references, I actually came across a very good book by the name of "Zen Buddhism and Environmental Ethics" by Simon P. James. In my first pass of the book, I ran across this notion of "Deep Ecology" which asserts that our current environmental crisis cannot be solved by the application of more science and technology. Rather it requires a deep shift in western consciousness in how we view our place in nature. Apparently one of the first proponents of this idea was Lynn White a professor in Medieval History who in a 1967 issue of Science, wrote "The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis".

In White's essay I've found a interesting analysis of the psychological foundations for our current relationship with the environment. Upon first reading I became convinced that it was one of the direct influences on Daniel Quinn's amazing book Ishmael.

The underlying idea is that the roots of modern science lie inside a Christian world view, which focuses on Man's quest to dominate, understand and subvert nature. The closing of the class gap has put the need and desire for technology in touch with the higher pursuits of pure science. Like gasoline on a fire, we've exploded in capability and population as a result of this, and even though the concerns of over-population and the environment are relatively new ones, we've been sowing the seeds of our destruction for hundreds of years.

As a beginning we should try to clarify our thinking by looking, in some historical depth, at the presuppositions that underlie modern technology and science. Science was traditionally aristocratic, speculative, intellectual in intent; technology was lower-class, empirical, action-oriented. The quite sudden fusion of these two, towards the middle of the 19th century, is surely related to the slightly prior and contemporary democratic revolutions which, by reducing social barriers, tended to assert a functional unity of brain and hand. Our ecologic crisis is the product of an emerging, entirely novel, democratic culture. The issue is whether a democratized world can survive its own implications. Presumably we cannot unless we rethink our axioms.

One of the things which struck me about this excerpt is the striking resemblance of "brain and hand" with MIT's slogan "Mens et Manus" -- "Mind and Hand."

Especially in its Western form, Christianity is the most anthropocentric religion the world has seen. As early as the 2nd century both Tertullian and Saint Irenaeus of Lyons were insisting that when God shaped Adam he was foreshadowing the image of the incarnate Christ, the Second Adam. Man shares, in great measure, God's transcendence of nature. Christianity, in absolute contrast to ancient paganism and Asia's religions (except, perhaps, Zorastrianism), not only established a dualism of man and nature but also insisted that it is God's will that man exploit nature for his proper ends.

At the level of the common people this worked out in an interesting way. In Antiquity every tree, every spring, every stream, every hill had its own genius loci, its guardian spirit. These spirits were accessible to men, but were very unlike men; centaurs, fauns, and mermaids show their ambivalence. Before one cut a tree, mined a mountain, or dammed a brook, it was important to placate the spirit in charge of that particular situation, and to keep it placated. By destroying pagan animism, Christianity made it possible to exploit nature in a mood of indifference to the feelings of natural objects.

And some people wonder why I'm a pagan.

The Greeks believed that sin was intellectual blindness, and that salvation was found in illumination, orthodoxy--that is, clear thinking. The Latins, on the other hand, felt that sin was moral evil, and that salvation was to be found in right conduct. Eastern theology has been intellectualist. Western theology has been voluntarist. The Greek saint contemplates; the Western saint acts. The implications of Christianity for the conquest of nature would emerge more easily in the Western atmosphere.

I was not aware of this divide even within the church. I suppose it goes to show what an evolving, self-selecting entity religion can be. It also points to why it so hard to say matter-of-factly "I am Christian." What breed of Christian? What time and place of Christianity are you referring to? In many ways, I find the gnostic and early Christian ideas incredibly interesting. I might even say I'd believe in some of their ideas, but it seems frightening to me to then say that I am Christian.

But since God had made nature, nature also must reveal the divine mentality. The religious study of nature for the better understanding of God was known as natural theology. In the early Church, and always in the Greek East, nature was conceived primarily as a symbolic system through which God speaks to men: the ant is a sermon to sluggards; rising flames are the symbol of the soul's aspiration. The view of nature was essentially artistic rather than scientific.

Ditto. Then enters the big bad Latin West --

However, in the Latin West by the early 13th century natural theology was following a very different bent. It was ceasing to be the decoding of the physical symbols of God's communication with man and was becoming the effort to understand God's mind by discovering how his creation operates. The rainbow was no longer simply a symbol of hope first sent to Noah after the Deluge: Robert Grosseteste, Friar Roger Bacon, and Theodoric of Freiberg produced startlingly sophisticated work on the optics of the rainbow, but they did it as a venture in religious understanding. From the 13th century onward, up to and including Leibnitz and Newton, every major scientist, in effect, explained his motivations in religious terms. Indeed, if Galileo had not been so expert an amateur theologian he would have got into far less trouble: the professionals resented his intrusion. And Newton seems to have regarded himself more as a theologian than as a scientist. It was not until the late 18th century that the hypothesis of God became unnecessary to many scientists.

The hypothesis may now be unnecessary, but the view of conquest and understanding remains.

If so, then modern Western science was cast in a matrix of Christian theology.

Professor White, then brings us the bad news:

I personally doubt that disastrous ecologic backlash can be avoided simply by applying to our problems more science and more technology. Our science and technology have grown out of Christian attitudes toward man's relation to nature which are almost universally held not only by Christians and neo-Christians but also by those who fondly regard themselves as post-Christians. Despite Copernicus, all the cosmos rotates around our little globe. Despite Darwin, we are not, in our hearts, part of the natural process. We are superior to nature, contemptuous of it, willing to use it for our slightest whim.

I can only hope that he is wrong, and there are some indications that he is wrong. The environmental movement spurred by essays like this one have reached the shores of scientists and politicians and (some of us) are working fast to correct our poor steering of the past few centuries. The human mind has produced some incredible good and I am optimistic enough to think that we will develop some brilliant inventions to reduce our impact on this world and stabilize our place on this little blue marble.

I have no doubt that life on Earth will survive until our solar system suffers from a cold death in a few billion years, it is only a question of whether or not humans will outlast the next few centuries.

What I envision is a scientific-enlightened citizenry that adopts some of the more buddhist and animist ways of thinking, in an effort to live in harmony with other life on Earth. By wedding mind and hand, we did more than we knew better to do, but our consciousness is catching up with our capabilities and I can only hope that a wedding of mind and spirit will be able right the wrongs of the past.

My 21W.775 - Writing about Nature and Environmental Issues, is the first humanities class I've taken at MIT that is NOT a philosophy class. Believe me ladies and gentlemen, that I would have never ventured outside the lofty domains of Course 24 - Philosophy and Linguistics, is it hadn't been for the wretched "HASS-D" requirement of MIT, that requires that I explore at least 3 flavors of the same ice cream: Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences.

What have I done to negotiate this forced exposure to other fields? Crafted the class into my own philosophy course of course! So far I've successfully been able to dictate my own philosophical-personal style of writing and have been received warmly. For an upcoming 10-12 page research paper, we've been asked to investigate some environmental issue of something relating to this area. My chosen topic is the Environmental Ethics of Zen Buddhism. Ha! Take that for forcing me to follow an assignment!

In my search for references, I actually came across a very good book by the name of "Zen Buddhism and Environmental Ethics" by Simon P. James. In my first pass of the book, I ran across this notion of "Deep Ecology" which asserts that our current environmental crisis cannot be solved by the application of more science and technology. Rather it requires a deep shift in western consciousness in how we view our place in nature. Apparently one of the first proponents of this idea was Lynn White a professor in Medieval History who in a 1967 issue of Science, wrote "The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis".

In White's essay I've found a interesting analysis of the psychological foundations for our current relationship with the environment. Upon first reading I became convinced that it was one of the direct influences on Daniel Quinn's amazing book Ishmael.

The underlying idea is that the roots of modern science lie inside a Christian world view, which focuses on Man's quest to dominate, understand and subvert nature. The closing of the class gap has put the need and desire for technology in touch with the higher pursuits of pure science. Like gasoline on a fire, we've exploded in capability and population as a result of this, and even though the concerns of over-population and the environment are relatively new ones, we've been sowing the seeds of our destruction for hundreds of years.

As a beginning we should try to clarify our thinking by looking, in some historical depth, at the presuppositions that underlie modern technology and science. Science was traditionally aristocratic, speculative, intellectual in intent; technology was lower-class, empirical, action-oriented. The quite sudden fusion of these two, towards the middle of the 19th century, is surely related to the slightly prior and contemporary democratic revolutions which, by reducing social barriers, tended to assert a functional unity of brain and hand. Our ecologic crisis is the product of an emerging, entirely novel, democratic culture. The issue is whether a democratized world can survive its own implications. Presumably we cannot unless we rethink our axioms.

One of the things which struck me about this excerpt is the striking resemblance of "brain and hand" with MIT's slogan "Mens et Manus" -- "Mind and Hand."

Especially in its Western form, Christianity is the most anthropocentric religion the world has seen. As early as the 2nd century both Tertullian and Saint Irenaeus of Lyons were insisting that when God shaped Adam he was foreshadowing the image of the incarnate Christ, the Second Adam. Man shares, in great measure, God's transcendence of nature. Christianity, in absolute contrast to ancient paganism and Asia's religions (except, perhaps, Zorastrianism), not only established a dualism of man and nature but also insisted that it is God's will that man exploit nature for his proper ends.

At the level of the common people this worked out in an interesting way. In Antiquity every tree, every spring, every stream, every hill had its own genius loci, its guardian spirit. These spirits were accessible to men, but were very unlike men; centaurs, fauns, and mermaids show their ambivalence. Before one cut a tree, mined a mountain, or dammed a brook, it was important to placate the spirit in charge of that particular situation, and to keep it placated. By destroying pagan animism, Christianity made it possible to exploit nature in a mood of indifference to the feelings of natural objects.

And some people wonder why I'm a pagan.

The Greeks believed that sin was intellectual blindness, and that salvation was found in illumination, orthodoxy--that is, clear thinking. The Latins, on the other hand, felt that sin was moral evil, and that salvation was to be found in right conduct. Eastern theology has been intellectualist. Western theology has been voluntarist. The Greek saint contemplates; the Western saint acts. The implications of Christianity for the conquest of nature would emerge more easily in the Western atmosphere.

I was not aware of this divide even within the church. I suppose it goes to show what an evolving, self-selecting entity religion can be. It also points to why it so hard to say matter-of-factly "I am Christian." What breed of Christian? What time and place of Christianity are you referring to? In many ways, I find the gnostic and early Christian ideas incredibly interesting. I might even say I'd believe in some of their ideas, but it seems frightening to me to then say that I am Christian.

But since God had made nature, nature also must reveal the divine mentality. The religious study of nature for the better understanding of God was known as natural theology. In the early Church, and always in the Greek East, nature was conceived primarily as a symbolic system through which God speaks to men: the ant is a sermon to sluggards; rising flames are the symbol of the soul's aspiration. The view of nature was essentially artistic rather than scientific.

Ditto. Then enters the big bad Latin West --

However, in the Latin West by the early 13th century natural theology was following a very different bent. It was ceasing to be the decoding of the physical symbols of God's communication with man and was becoming the effort to understand God's mind by discovering how his creation operates. The rainbow was no longer simply a symbol of hope first sent to Noah after the Deluge: Robert Grosseteste, Friar Roger Bacon, and Theodoric of Freiberg produced startlingly sophisticated work on the optics of the rainbow, but they did it as a venture in religious understanding. From the 13th century onward, up to and including Leibnitz and Newton, every major scientist, in effect, explained his motivations in religious terms. Indeed, if Galileo had not been so expert an amateur theologian he would have got into far less trouble: the professionals resented his intrusion. And Newton seems to have regarded himself more as a theologian than as a scientist. It was not until the late 18th century that the hypothesis of God became unnecessary to many scientists.

The hypothesis may now be unnecessary, but the view of conquest and understanding remains.

If so, then modern Western science was cast in a matrix of Christian theology.

Professor White, then brings us the bad news:

I personally doubt that disastrous ecologic backlash can be avoided simply by applying to our problems more science and more technology. Our science and technology have grown out of Christian attitudes toward man's relation to nature which are almost universally held not only by Christians and neo-Christians but also by those who fondly regard themselves as post-Christians. Despite Copernicus, all the cosmos rotates around our little globe. Despite Darwin, we are not, in our hearts, part of the natural process. We are superior to nature, contemptuous of it, willing to use it for our slightest whim.

I can only hope that he is wrong, and there are some indications that he is wrong. The environmental movement spurred by essays like this one have reached the shores of scientists and politicians and (some of us) are working fast to correct our poor steering of the past few centuries. The human mind has produced some incredible good and I am optimistic enough to think that we will develop some brilliant inventions to reduce our impact on this world and stabilize our place on this little blue marble.

I have no doubt that life on Earth will survive until our solar system suffers from a cold death in a few billion years, it is only a question of whether or not humans will outlast the next few centuries.

What I envision is a scientific-enlightened citizenry that adopts some of the more buddhist and animist ways of thinking, in an effort to live in harmony with other life on Earth. By wedding mind and hand, we did more than we knew better to do, but our consciousness is catching up with our capabilities and I can only hope that a wedding of mind and spirit will be able right the wrongs of the past.

Labels:

christianity,

deep ecology,

environment,

Lynn White,

nature,

people,

philosophy,

religion

Tuesday, October 9, 2007

R&R After a Week of Hell

I have to confess it. This past week was one of the most grueling, exhausting, and all around depressing weeks I've ever experienced as an undergraduate. One of those weeks where you say to yourself before hand, this is going to be one of the most preposterous weeks you'll ever experience and somehow when you're actually in the middle of it, you forget those words of caution that you gave yourself. There were times when I felt like my hopes and ambitions to become a mathematician were crumbling down around me and that I was going to have to give it all up and figure out something else to do. When the going was at its toughest, perspective was just something I couldn't have.

I'm recovering from that slump, and most of it can be attributed to having a 4-day weekend and spending my first day in a long time where I did absolutely NO work. A truly amazing feeling, I almost forgot what it was like. So what did I do with my day of rest and relaxation you might ask? I took pictures of course!

The MIT Museum has recently had a "Grand Re-Opening" and introduced several new exhibits including several technical toys from the personal collection of Claude Shannon, information theorist extraordinaire.

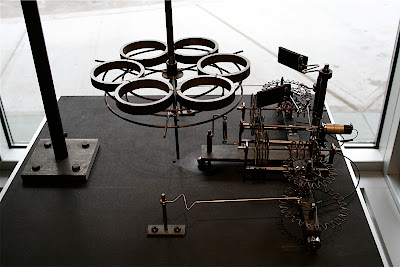

The kinematic sculptures of Arthur Ganson was a usual treat. The photo above is of a rather haunting piece named "Alone" where the complex gear network below causes the figurine to slowly move away (or towards) the edge.

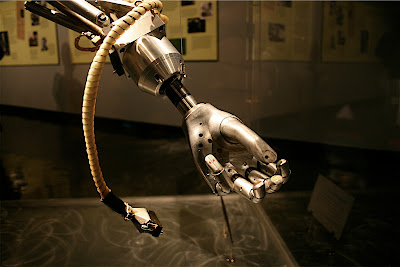

The arm above, known as "Minsky Arm," was the second arm developed by Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert in a several year project to develop a computer which could see and interact with objects independent of human control. The amount of humanity which was instilled in its craftsmanship, is truly amazing. The relaxed state of the arm feels graceful and beautiful to me, as if I were admiring some fresco in the Vatican.

The self-oiling sculpture is one of my favorites of Ganson's. This machine is able to maintain itself, feed itself oil, it features of the complex self-referential process of homeostasis that distinguishes living things from the normally robotic.

This push cart seems to be an incredible satire on the constant rush and desire to get ahead and today's materialistic capitalist world. It is built like a heavy-duty baby carriage (or "pram" for you British) that writes out a message on a piece of paper as you push it. On closer inspection (below) the message is the instruction "faster!" This is just another example of the sort of recursive self-creating art that I've grown to appreciate.

Upon disembarking from the MIT Museum, I felt my photo-taking hunger was not satisfied. I then remembered this crazy house on Brookline that I've been meaning to document for several months now.

The house is this wonderfully strange purple reminder of "cosmic consciousness" and the sort of playful insight gained and distributed by the "Beautiful People" of the 60s and 70s. This island in Cambridge remains. The slideshow above will give you a feel for the house, but I was very careful to document the whole fence and have uploaded the original size. Feel free to zoom in on the photos in my picasaweb and examine the detailed sayings on the fence. Please be patient as each photo is nearly 5mb in size, but the tapestry of this fence's wisdom is worth the wait. Some of my favorite nuggets are: "Serious Governments always fail", "The Cosmic Goose", "use of paraphenomenal abilities is a normal capacity among all advanced Galactic Civilizations, but Hyperspace is the frosting on the cake", "Twosday is Primeval, the egg is weavel", "competition Vs. Producing things which are cosmically beautiful", "generally speaking disorderly terrain reflects the truest Reality", the list just goes on. But what is this house? I don't know. It claims to be the "Center for Intergalactic Fragmentational Revurberations", but when I told my parents that I was applying there for graduate school they seemed suspicious. Perhaps the "National Defense Center Against Leaders: you're in charge" would be more pleasing to their palate, I think not.

Leaving the house of "Cosmic Structure" behind, I had to refuel. So coffee and pastries were in order. This gorgeous middle eastern restaurant and hooka bar, certainly filled the bill.

I did a random walk through west Cambridge before ending up in Harvard Square, where the alcohol-free, Puritanical verson of Oktoberfest was being held. Aside from my encounter with a giant bunny rabbit in a suit, the event was pretty tame.

Perhaps it was the non-alcoholic beer I had, or some suspect sausage, everything started to take on funny colors, so I decided to head home. Fortunately, heading home, my camera agreed with my altered state. At least it made for beautiful pictures. I hope you enjoy my subjective take on reality!

I'm recovering from that slump, and most of it can be attributed to having a 4-day weekend and spending my first day in a long time where I did absolutely NO work. A truly amazing feeling, I almost forgot what it was like. So what did I do with my day of rest and relaxation you might ask? I took pictures of course!

The MIT Museum has recently had a "Grand Re-Opening" and introduced several new exhibits including several technical toys from the personal collection of Claude Shannon, information theorist extraordinaire.

The kinematic sculptures of Arthur Ganson was a usual treat. The photo above is of a rather haunting piece named "Alone" where the complex gear network below causes the figurine to slowly move away (or towards) the edge.

The arm above, known as "Minsky Arm," was the second arm developed by Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert in a several year project to develop a computer which could see and interact with objects independent of human control. The amount of humanity which was instilled in its craftsmanship, is truly amazing. The relaxed state of the arm feels graceful and beautiful to me, as if I were admiring some fresco in the Vatican.

The self-oiling sculpture is one of my favorites of Ganson's. This machine is able to maintain itself, feed itself oil, it features of the complex self-referential process of homeostasis that distinguishes living things from the normally robotic.

This push cart seems to be an incredible satire on the constant rush and desire to get ahead and today's materialistic capitalist world. It is built like a heavy-duty baby carriage (or "pram" for you British) that writes out a message on a piece of paper as you push it. On closer inspection (below) the message is the instruction "faster!" This is just another example of the sort of recursive self-creating art that I've grown to appreciate.

Upon disembarking from the MIT Museum, I felt my photo-taking hunger was not satisfied. I then remembered this crazy house on Brookline that I've been meaning to document for several months now.

The house is this wonderfully strange purple reminder of "cosmic consciousness" and the sort of playful insight gained and distributed by the "Beautiful People" of the 60s and 70s. This island in Cambridge remains. The slideshow above will give you a feel for the house, but I was very careful to document the whole fence and have uploaded the original size. Feel free to zoom in on the photos in my picasaweb and examine the detailed sayings on the fence. Please be patient as each photo is nearly 5mb in size, but the tapestry of this fence's wisdom is worth the wait. Some of my favorite nuggets are: "Serious Governments always fail", "The Cosmic Goose", "use of paraphenomenal abilities is a normal capacity among all advanced Galactic Civilizations, but Hyperspace is the frosting on the cake", "Twosday is Primeval, the egg is weavel", "competition Vs. Producing things which are cosmically beautiful", "generally speaking disorderly terrain reflects the truest Reality", the list just goes on. But what is this house? I don't know. It claims to be the "Center for Intergalactic Fragmentational Revurberations", but when I told my parents that I was applying there for graduate school they seemed suspicious. Perhaps the "National Defense Center Against Leaders: you're in charge" would be more pleasing to their palate, I think not.

Leaving the house of "Cosmic Structure" behind, I had to refuel. So coffee and pastries were in order. This gorgeous middle eastern restaurant and hooka bar, certainly filled the bill.

I did a random walk through west Cambridge before ending up in Harvard Square, where the alcohol-free, Puritanical verson of Oktoberfest was being held. Aside from my encounter with a giant bunny rabbit in a suit, the event was pretty tame.

Perhaps it was the non-alcoholic beer I had, or some suspect sausage, everything started to take on funny colors, so I decided to head home. Fortunately, heading home, my camera agreed with my altered state. At least it made for beautiful pictures. I hope you enjoy my subjective take on reality!

Labels:

Art,

camera,

Claude Shannon,

Cosmic Moose,

Frank,

Harvard Square,

MIT Museum,

photos

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)